When Alan Lomax and the Tobagonion folklorist J.D. Elder visited Trinidad in the Spring of 1962, the island’s independence from Great Britain was just months away and Trinidadians were swept up in a joyful spirit of expectation and national pride. The pair’s recordings are breathtaking in both fidelity and diversity and, taken as a whole, they offer what was arguably the first panoramic view of the depth and breadth of the island’s expressive traditions, specifically those of the Carnival (Shrovetide) season. Here, in collaboration with Brooklyn organization JouvayFest, we trace the emergence of Carnival and a distinctly Afro-Trinidadian Shrovetide music—that of j’ouvert (also spelled jouvay or juvé)—through the lens of Lomax and Elder's 1962 recordings.

Much of the text of this exhibit has been liberally adapted from John Cowley's liner notes to Trinidad: Carnival Roots (Rounder Records, 2010). Any errors are ours.

A History of Carnival

The Shrovetide Carnival, the period in the Christian calendar when sins are shriven—that is, confessed and absolved—marks the division between winter indulgence and springtime abstinence. Pre-Lenten Carnival activities in Trinidad generally begin with Dimanche Gras, Lundi Gras, and culminating with Mardi Gras (Shrove Tuesday). The end of the celebration is signaled by Ash Wednesday, the start of Lent, a 40-day period of fasting and penitence that lasts until Easter. This calendar is set by elements of the Gregorian Calendar, so Ash Wednesday's date changes every year. Antithetical both to Christian spiritual values and its period of physical abstinence, the Shrovetide bacchanal crosses a divide between secular gratification and sacred sensibility, accommodating the sometimes-delicate relationship between Church and State, and complicated by the split between Roman Catholic and Protestant churches. Coincidentally, the most persistent Black musical evolutions in the Caribbean are associated with sacred or secular events that frequently combine together, as with Carnival. These creolized musical forms are rich sources of evidence of cross-fertilization stemming from the world diaspora to the Americas and are prominent in the Trinidad festival and similar celebrations in the region.

The Trinidad Carnival is an amalgam of customs imported by migrants and is tied intimately to the history of the region. Shrovetide activity commenced after the Spanish invaded the island in 1492. Indigenous inhabitants, including the Arawaks and Caribs, who had been converted to Catholicism by Spanish colonists, lived in a very thinly populated territory until migrant plantation owners brought an enslaved African-Caribbean workforce in the late 1700s. Many planters and their slaves came to Trinidad from French Caribbean islands and were officially Roman Catholic, a requirement for settlement. Influenced by the experience of slavery and by contact with European conventions, they brought with them a creole culture which was sustained in Trinidad until the early 1900s. Thus, French Creole was in widespread use as a lingua franca for well over a century after the conquest of the island by Britain in 1797, and Roman Catholicism is still practiced today.

Afro-Trinidadian participation in the island festival came of age following Emancipation (1834) and more particularly after the ending of Apprenticeship (British legislation that bound the newly emancipated slaves to plantations as “apprentices” until the passage of an amendment in 1838 put an end to this iniquity). From that point on, evolving circumstances triggered musical innovation and other cultural changes. Nineteenth-century historical accounts of Carnival document and date the appearances of successive migrant groups, portrayed both in parody and admiration, in the celebration.

The castilians and pasillos were the fare of Carnival dances; the rhythm of the latter was the same as calypso. Trinidad’s primary vocal style, calypso is distinguished by linguistic power and verbal dexterity, wit, and improvisation, and is just one of a number of West Indian traditions that feature wordsmith technique. Loosely, these fall into two categories, one emphasizing eloquence, the other characterized by competitive invective. Lomax and Elder documented examples of both in several of the islands they visited in 1962.

In Lopinot they recorded a Venezuelan-influenced repertoire played by Sotario Gómez and other musicians. Gómez arranged a session of secular and sacred string band music that included “Pasillo,” a tour-de-force equal to any secular occasion on the island for which the group might have performed. The rhythm of “Pasillo” is that of the paseo or two-step, and its melody is close to that of “Is Trouble [In Arima],” a stick-fighting song recorded in England in the early 1950s by the calypsonian Lord Kitchener (Melodisc 1310).

The calypso is fundamentally a song of the people, a popular art form that has persisted through two centuries in part because it has functioned as a powerful means of expression for diverse ethnic groups who, when they were thrown together in a new land, struggled and fought for political liberty.

Detailed descriptions of Carnival songs are difficult to discover in nineteenth-century sources. The first located mention of the word ‘callisos’ describes dances performed during the Carnival of 1876. There are later citations with the same meaning. By 1898 ‘calypso’ was used just prior to the festival to refer to a form of song. Reference to “double tone” calipso (a variant spelling) is made in the Port-of-Spain Gazette which prints an early text in the lead-up to the Carnival of 1900. Sung in either major or minor keys, double tone calypsos had seven- or eight-line stanzas, comprising two parts, with the first line repeated in the initial section. This was known as the oratorical pattern, or “oration” style. Calypsos sung in French Creole were known as “single tones” and were likewise performed in major or minor keys but had four lines in each verse. Songs chanted in the streets by carnival bands were called lavways or leggos and generally evolved from old-time kalendas.

Lomax recorded a second session with the Sotario Gómez Orchestra, also known as Los Parenderos [possibly an alternate spelling of Parranderos], in Lopinot on May 4th. Gómez led on fiddle, with cuatro by Pedro Segundo Dolaballie, complemented by guitar, bass cello, and maracas. The resulting sound is very similar to that of the bands that accompanied calypso singers in the early decades of the twentieth century and contrasts markedly with Dolaballie’s version. This particular “Venezuela vals” is a version of a composition recorded by the famous Trinidad violinist Cyril Monrose in New York in 1923 (Victor 77052).

In areas influenced by African and French culture, several “old creole” drum dances evolved during slavery, notably the belair (bélè), calenda (kalenda/kalinda), and juba. Elements of these familiar song styles and dances were incorporated into the Trinidad Carnival. In a celebration marking the ending of slavery, bacchanal activities commenced at midnight on Shrove Sunday with a torchlight procession called Cannes Brulées / Canboulay. Masques included representations of enslavement, devils, and of death. While drummers played and women with shac-shacs (maracas) sang belairs, members of each stick band fought one another (hallé baton), and the crowd danced corlindas (old kalenda).

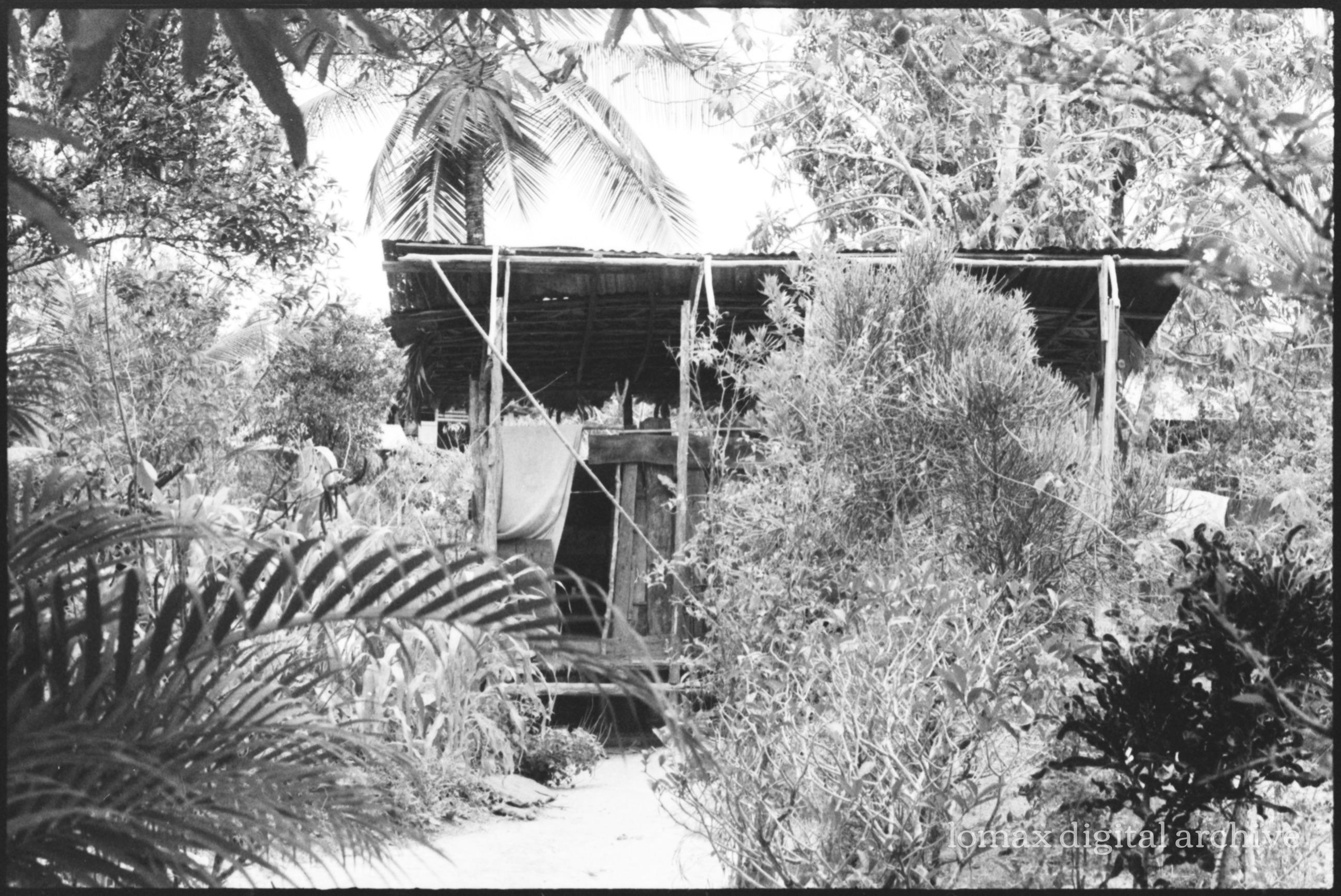

The belair (or bélè) is an old creole drum dance that, like the kalenda, contributed to the evolution of calypso. The genre is known in all the French Creole speaking islands of the Eastern Caribbean, and Lomax recorded variants in seven of the twelve territories he visited in 1962. The belair in Trinidad developed as a local secular festival presided over by an elected King and Queen (in the manner of Fancy Carnival bands during the early 1900s), with the drummers housed in traditional temporary structures made from palm fronds—precursors of the calypso tent. Then as now, women dancers wore elaborate creole costumes; similarly, the men were smartly dressed. Like calypso, belair texts often contain social commentary. Led by Mickey Bentic, the belair group recorded by Lomax in 1962 was formally trained, although one of the drummers played at the kalenda session in the same vicinity (Mayaro Bay). The rhythmic “We Yo Ka Monte, Sewe!” represents part of their repertoire of traditional dances.

Such tunes formed a reserve from which calypsos were composed. Alfred Codallo's special string band dipped into this pool of melodies for a traditional paseo that the musicians identified as “Ram Goat Baptism,” a highly popular calypso from the late 1940s. Composed and recorded by The Wonder (Victor Attwell) (originally issued in 1949 on Kiskidee 5004 with accompaniment by George Mootoo & His Orchestra), this song tells of a scandal associated with Brother Willie (Joseph King) of the Spiritual Baptist Church—then a proscribed organization. The lyrics to this song give an idea of the mockery and ribald satire associated with the genre.

Paseo

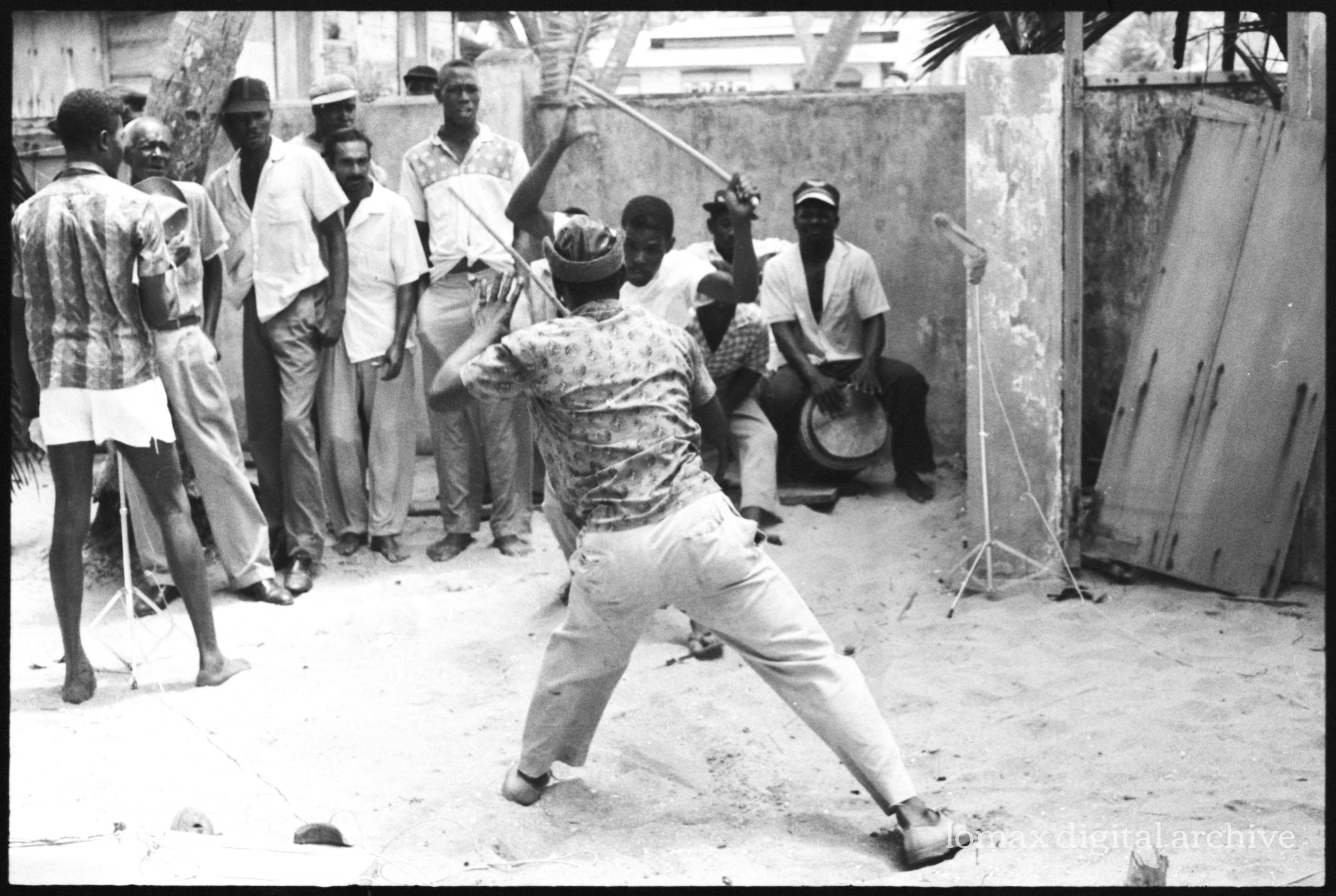

The use of the word kalenda to denote fighting activity seems to date from the late-nineteenth century. The term represents music to accompany quarter-staff dueling and by extension the dueling itself.

As late as the 1910s, stick fighters were considered part of the diametre, or underworld, and treated accordingly by the authorities. Life was held cheaply in this milieu, and incarceration and/or early death were common.

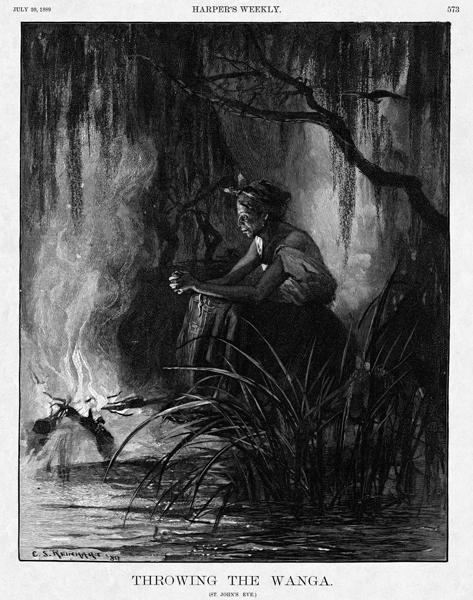

The spiritual practice of obeah, also known in Trinidad as wanga, is an element of African-diaspora tradition that became commonplace throughout the West Indies. The stick fighters used wanga in the preparation of their fighting implements. Cut from tropical hardwoods such as anaré, poui, and gasparee, ritually treated sticks were buried in graveyards for a set period before use.

In administrative moves to curtail the bands, canboulay, and drumming during Carnival parades were prohibited from 1884; drums at dances were also controlled by license. This limited the form of rhythmic accompaniment for stick bouts, and an extraordinary substitute was found, probably in the 1890s, in the form of stamping tubes, known as tamboo bamboo (or bamboo tamboo). These comprise a consort of three types of bamboo tubes, distinct in length and diameter, through which the air moves to produce notes of different timbre when the tubes are pounded on the ground. Sticks struck against the sides of the tubes and bottles beaten with spoons provide extra resonance. Stick-fighting kalenda and tamboo bamboo represent the defiant and sometimes violent extremity of Black Creole society that did not conform with colonial notions of decorum. The units are precursors of contemporary Trinidad steel bands. In Port of Spain players of the boom or bass bamboo would strike their instruments on the metal tracks of the streetcar lines, which augmented the resonance and defiant message of both lyrics and music.

A local Tamboo Bamboo band performing at Carnival in Trinidad. The Tamboo Bamboo band instruments are made up of cut bamboo and played with wooden sticks, a practice stemming from when drums were outlawed by the authorities.

From Calypso And The Evolution of Carnival: A Short History by J.D. Elder:

In the old days, the Spanish and French aristocrats celebrated Carnival, a grand fête, from Christmas to Ash Wednesday. The Negroes took no part in these festivities, nor could the Free Colored people participate. But after Emancipation in 1830, the ex-slave population began to celebrate August 1 (August Day) as Freedom Day in a pageant they called Cannes Brulées (French for “burnt canes”) or Canboulay. They played kalinda and marched in the streets in great bands, each of which had kings and queens, princes and princesses, and a mock royal retinue. The guards in attendance were the “stick men,” armed with flambeaux and poui (a type of wood) sticks. After some years, the Negroes switched the date of Cannes Brulées to coincide with that of the original European Carnival. This so upset the planter class that the authorities took steps to suppress Carnival itself in the hope of stamping out the drum music and torchlight procession of the Cannes Brulées pageant. They declared carrying of sticks by Negroes illegal. In attempting to enforce this law, however, the authorities came into conflict with the wishes of the majority of the populace – the Free Colored mulattoes, Negroes, Spanish, and English. The conflict was waged on the basis of class and not race, and the mulattoes supported the Negroes in resisting the restrictive laws.

By the 1880s the sentiments of the antagonists had reached fever pitch. The police attempted to arrest Cannes Brulées bands and warned that Captain Bake of the police intended to eliminate the pageant on Carnival Monday. The captain and his men and the revelers clashed and a riot ensued. The casualty list was high and included both policemen and civilians. This event was followed by attempts to suppress kalinda in urban and semi-urban districts. There was no sudden transformation, however, and kalinda singing and stick-playing have never really stopped in the rural areas of Trinidad.

Jean Eustache Stoute ran a local belair group on the north coast of the island in Blanchisseuse. At that time a relatively isolated community, cut off by the jungle and by the northern range of extinct volcanoes, Blanchisseuse was a haven for French Creole- and Venezuelan- (or “Spanish-”) influenced folk music. Tapping the rhythm on the table with her hand, Jean sang an old stick-fighting song, “Patizan-mwen i las,” about the adverse legal consequences of combat. The strong fatalism inherent in its message is common to many of these songs.

In the southeastern part of the island, in Mayaro Bay, J. D. Elder led Alan Lomax to Matthew Thomas, an old-time fighter and chantwell. His group comprised fishermen and laborers complemented by four accomplished drummers on ka (keg), or quarter-barrel drums. Lomax noted that the players sat astride their drums, “beating with both hands and damping with their heels.” The call-and-response vocals with drumming in “Regimen mwen de leon mama” demonstrate the African roots of stick songs. This is a challenge performance, in which the singer’s introspective references to joining his mother and father in death are juxtaposed with the pugilistic sentiment of the title, “My Lion Regiment,” a common thematic contrast in these performances.

Regimen mwen de leon mama

“Fire Brigade, Water the Road,” another nineteenth-century kalenda staple, was used as a challenge song directed at the authorities, specifically at the Fire Brigade, instituted in Port-of-Spain in 1859. During the heyday of confrontation between the stick bands, the Fire Brigade was called in to control the crowds and to reduce the resulting pall of swirling dust from unpaved streets.

In a post-performance interview, Mathew Thomas outlines the desperado character of the fighters and, after prompting, mentions the ritual tou sang (“blood hole”) into which wounded combatants collectively drained their blood. Andrew Pearse, in his "Hunting for History," (Kyk-Over-Al, Vol. 3, No. 12, 1951, pp. 210-211), gives a rationale for this practice: “If my blood falls on the ground and is dried by the sun, then the blood in my veins will dry up, and I shall sicken."

The significance of the lyrics of “Fire Brigade” remained potent for many years. In 1938 the celebrated calypsonian Atilla the Hun (Raymond Quevedo) cut a commercial recording of the song for Decca (Decca 17389). In 1939, anthropologists Melville and Frances Herskovits collected the kalenda “Wata Works,” a variant, in Toco, Trinidad. Arriving in England in 1953, a Trinidad soccer team employed it to challenge their opponents. It was still going strong in 1962, as can be heard performed by the Maraval Tamboo Bamboo Band below.

J'ouvert

J'ouvert—or Jouvay—is the pre-dawn celebration that marks the start of Carnival. (There is a conflation about the time J'ouvert commenced in Trinidad Carnival. Under colonial legislation, from 1884 it was not permitted until 6 a.m. This time was stipulated in the annual proclamations allowing the festival to take place. The rule would have been enforced vigorously in the late nineteen and early twentieth centuries when stick bands were still prevalent in festival parades. Almost certainly it was post-independence that the official time of commencement was changed to 4 a.m. There is a report in the Trinidad Guardian for February 13, 1934 (p. 1), however, that notes the ‘Old Masks’ were in the streets at 4 a.m.—two hours in advance of the official commencement of the festival—and from other accounts it seems that by the late 1930s the 6 a.m. rule was not aggressively enforced). Whether they started at 4 a.m. or 6 a.m., these daybreak festivities originated as post-emancipation rituals that featured torchlight Canboulay processions, one of the original pre-emancipation traditions that symbolizes the harvesting of burnt cane fields during slavery. In recent years, reenactments of the 1881 Canboulay Riots have become a part of the Jouvay celebrations, as can be seen here, in Port-of-Spain. Daytime Carnival, as it is celebrated today, is the extension of these traditional celebrations.

The term meaning ‘daybreak’ probably applies in other Carnivals in the French Creole-speaking Caribbean. Lafcadio Hearn heard it in Saint-Pierre, Martinique when he witnessed the Carnival there in 1888.

"Hearn also identifies a specific band that probably appeared only on mercredi des cendres [Ash Wednesday], and personified a particular French Creole legend reported from several islands, that of la diabless — a phantom woman of beauty who lures the unsuspecting male to his doom.1 The folk superstition is articulated by Hearn in association with his description of the band of diablesses he saw on the streets of Saint-Pierre in 1888. Few in number, for height was a special attribute in this masquerade, they were ‘robed all in black, with a white turban and white foulard,’ wore ‘black masks’ and carried ‘boms (large tin cans), which they allow[ed] to fall upon the pavement from time to time; and, they walk[ed] barefoot.’ The tallest deviless ‘always walk[ed] first, chanting the question, “Jou ouvè?” (Is it yet daybreak?) And all the others reply[ing] in chorus, “Jou pa’nco ouvè” (It is not yet day)’; a chant recalled from Trinidad Carnival celebrations in the early 1900s where the adapted masquerade was called Jour Ouvert. In Port-of-Spain, the band appeared in the initial parade, at daybreak (6.00 a.m.) on Shrove Monday, and members were dressed as the ‘proverbial witch’ with ‘tall hats, long black robes, and carried long sticks to lean on’.2"

1La Diabless legend: Dominica – Lennox Honychurch, Our Island Culture, Roseau, Dominica, Dominica Cultural Council, 2nd ed., Roseau, Dominica, Dominica National Cultural Council, 1988, pp. 44-45; Martinique – Hearn, ‘La Verette,’ p. 740; and the chapter ‘La Guiablesse’ in his Two Years, pp. 184-201; St. Lucia – Daniel J. Crowley, ‘Supernatural Beings In St. Lucia,’ Caribbean, Vol. VIII, No. 11, June-July 1955, pp. 241-244, 264-265; Trinidad – Armand Massé, ed. Dominique Rézeau, & Pierre Rézeau, De La Vendée aux Caraïbes: Le “Journal” (1878-1884) d’Amand Massé missionnaire apostolique, Vol. 1, Paris, Éditions L’Harmattan, 1995, [14 novembre 1879] pp. 319-320; Abbé Armand Massé, M. L. de Verteuil, trans., The Diaries of Abbé Armand Massé, Vol. 4, Port-of-Spain, privately published by the translator, 1988, [14 November 1879] pp. 328-329; L. O. In[n]is, ‘Folklore And Popular Superstition,’ in T. B. Jackson, ed., The Book Of Trinidad, Port-of-Spain, Muir Marshall & Company, 1904, pp. 114-115, 116

2 Hearn, ibid.; Charles Jones (Duke of Albany), Calypso & Carnival Of Long Ago & Today, Trinidad, Port-of-Spain Gazette, 1947, p. 21; see also the twentieth-century descriptions of the costume and performances by Les diablesses in Fort-de-France, Martinique in: Dufougeré, op. cit., infra fn. 131, and Labrousse, op. cit., p. 86

-from John Cowley, ‘Mascarade, biguine and the bal nègre,’ in Alain Boulanger, John Cowley and Marc Monneraye, comps., Creole Music of the French West Indies, A Discography, 1900-1959, Hambergen, Germany, Bear Family Publications, 2014, p. 225

Di Band is Comin!

Sandra A. M. Bell describes the excitement of hearing the band making its way down the street during the Jouvay procession in Trinidad.

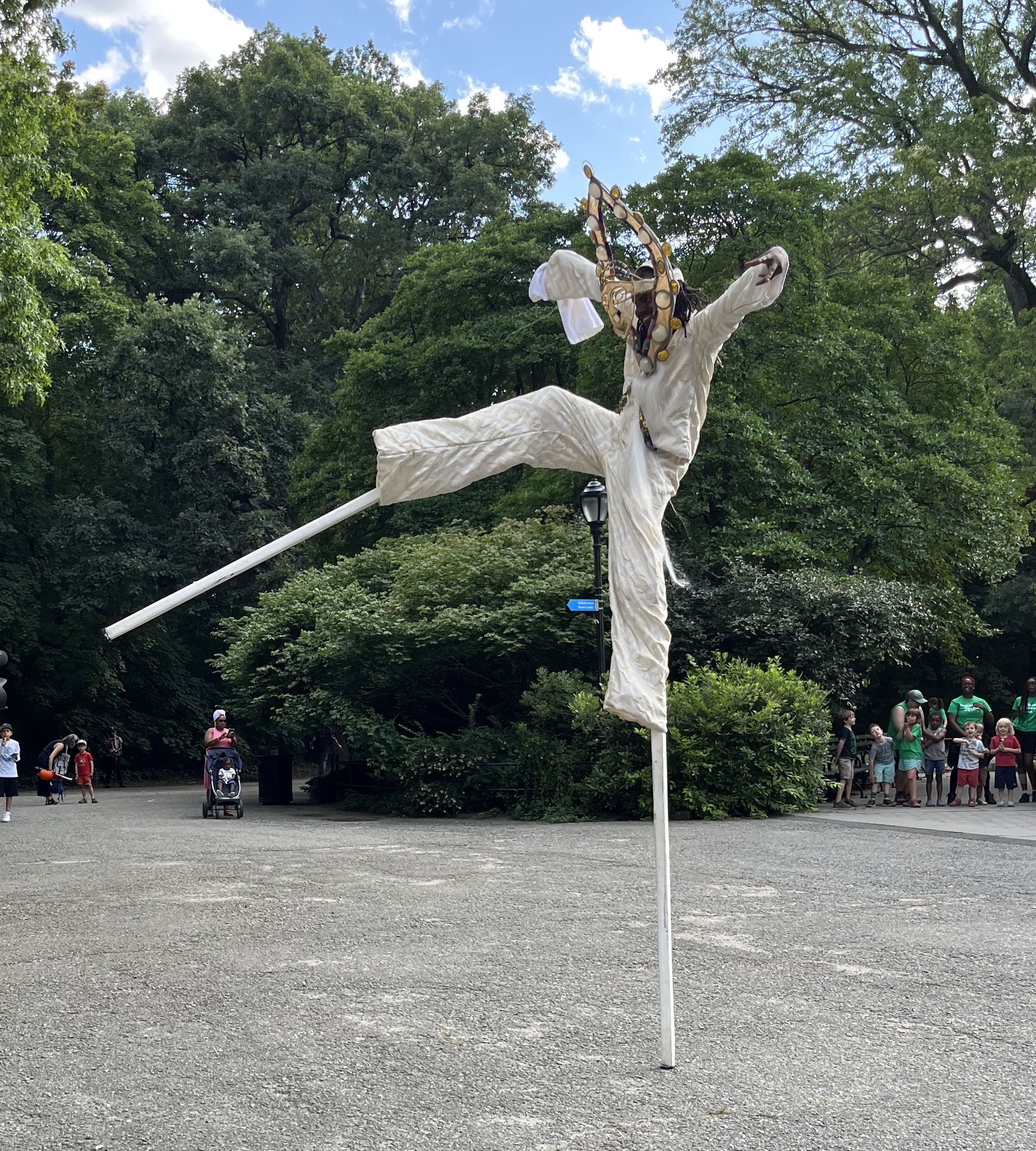

Through the traditional characters of J'ouvert—the speech-giving Midnight Robber, the jab jab devils covered in black oil, the voluptuous Dame Lorraines, the blue devils, the Pierrot Grenade—revelers can provide satirical political and social commentary using their costumes. Most costumed participants tend to stay with the same characters year after year, putting their own creative spin on the traditional archetypes.

The Midnight Robber is a speech-making character and appears to have developed from a cowboy masque during the first two decades of the twentieth century. Elaborated by numerous variations, his costume and other characteristics were based on portrayals of bad guys in pulp magazines published in the United States and Britain. Robbers traversed the streets in groups, “holding up” spectators demanding to be paid in “pounds” or, like their Pierrot counterparts, challenging masqueraders of the same class with ostentatious orations. Both representations are now virtually defunct, but in 1962 Elder and Lomax were fortunate to discover a gifted Midnight Robber in Vasco de Freitas, lead singer of the Maraval Tamboo Bamboo Band, who had been playing the mas’ (masque) for 21 years. Studies of “Robber” speeches show they are loosely formulaic but with great scope for improvisation.

Rollo The Ganja (Midnight Robber Carnival speech)

Elements of Midnight Robber speech, including the one by de Freitas above, made their way into innumerable calypsos and can be heard in such recordings as “Song No. 99” made by Houdini (Okeh 8621) and “Coquette” (Gennett 20359) and by King Radio (Norman Span), the Tiger, and the Lion in “Don’t Break It, I Say” (Decca 1728). In costume and under the sobriquet Rollo The Ganja, de Freitas roamed the streets of Port-of-Spain and Maraval during Carnival, challenging other “robbers” with fearsome speeches and soliciting “treasure” from onlookers by the same technique. After recording one of de Freitas’s performances Lomax wrote in his notes: “Long piece of tall speech – a brag that makes Davy Crockett look like a piker,” adding, that in contrast with his utterances, “the speaker. . . is slight, thin, snaggletooth, in rags – a more nondescript figure could not be imagined.”

Prompted by J. D. Elder, de Freitas talks about his Carnival apparel, the nature of his character, Rollo the Ganja, and his escapades.

Carnival Competition Reminiscences

Here, Sandra A. M. Bell recalls her experience in a costume competition for her character of Counting Jab Jab.

"It's dedicated to all the Black people who were killed unarmed by police here in America. The costume had ribbons with every one of these people's names on it coming out of the horns and flowing down the back."

The costume is always being updated — as the body count grows, the ribbons are added.

Sandra A. M. Bell as The Counting Jab Jab. Photo courtesy of JouvayFest Collective.

Carnival tents, run by individual carnival bands and later organized independently by teams of songsters, became a continuing attraction of the pre-Carnival season. Here calypsonians presented their annual topical and other compositions for audience approval. Each entertainment ended with a “war” or picong in the manner of the verbal contests between nineteenth-century Pierrots and other characters, such as the Actor Boys in the pre-Emancipation Jonkonnu of Jamaica (a Christmas festival similar to Carnival, held in African diasporic communities in the Caribbean and southeastern United States). This pattern is part of a larger family of African and circum-Mediterranean traditions of debates, arguments, and contests in poetry and song, including the Dozens tradition in the US. Calypso singers improvised stanzas in disparaging their rivals and exalting themselves and endeavored to force an opponent into making an error, thus bringing about his exclusion from the contest. In the guise of Rollo the Ganja, Vasco de Freitas refers to the technique in his Midnight Robber speech:

or in a picong during a calypso war,

when your paltry verses are done,

with your dunce head I will have some fun.

I will give you rocks to eat for bread

and you will be numbered among the dead.

Competitive verbal contests in Carnival are phenomena of long standing. In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, the Pierrot, pays roi, or country king, was the most prominent practitioner. This character appears to have been an amalgam of the European masque known as Pulcinella with the territorial leadership of stick bands. Gorgeously dressed in gown and cap (padded for protection), each Pierrot cleared the way before him by cracking his long whip. He was accompanied by a Page Boy (sometimes cast as his paramour) carrying a stick. His stick band followed in formation. Pierrot confrontations began with bombastic speeches, with each opposing Pierrot proclaiming himself king and seeking a rival. This was followed by combats à la ligueze (whip lashings) and finally stick fighting. The legislation that prohibited canboulay separated the bands from the Pierrot contests, which were controlled by regulation after 1892.

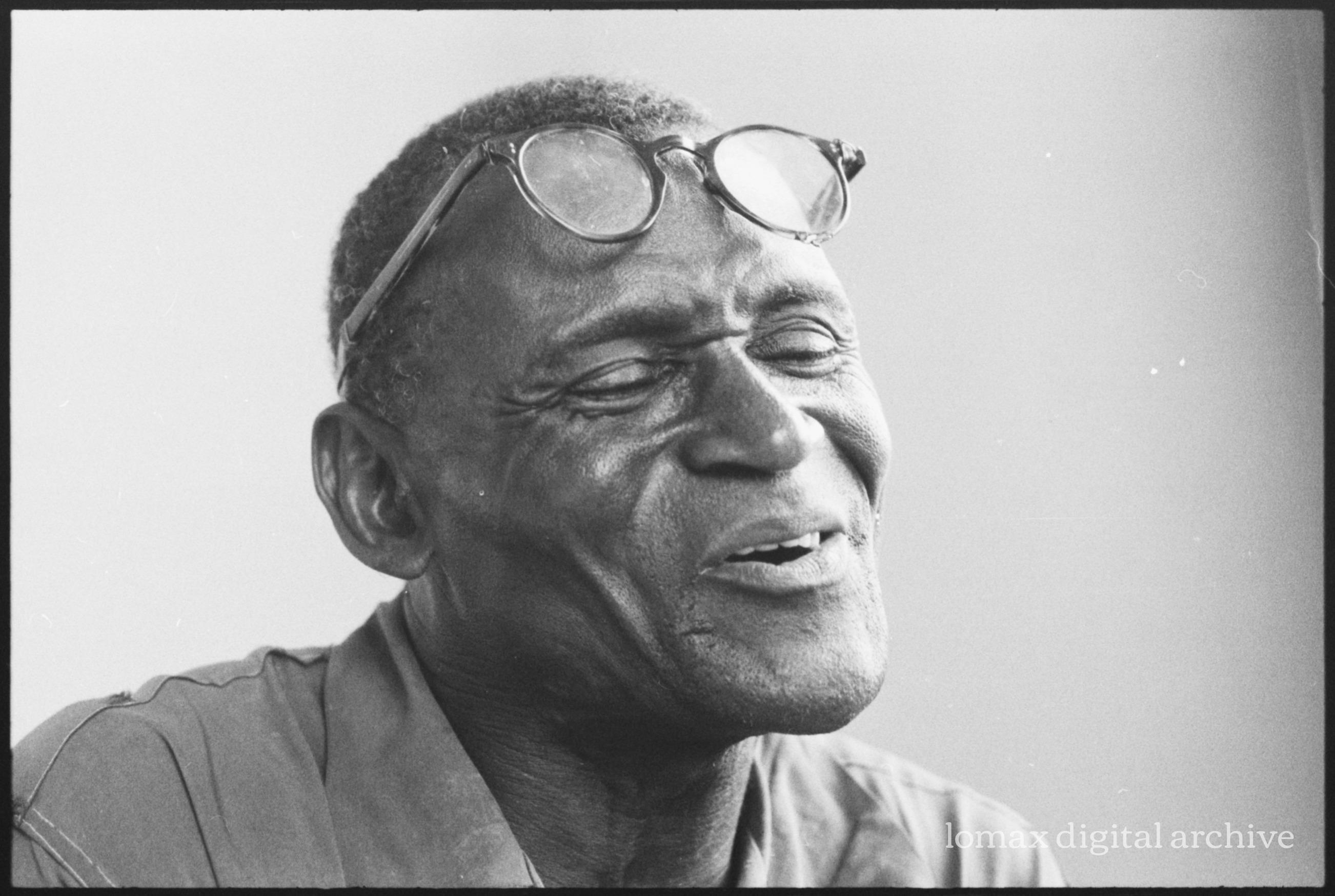

Only a small number of these calypso wars were ever recorded commercially; Alan Lomax actually managed to stage one such encounter at his Calypso at Midnight Concert in New York in 1946. During this 1962 field trip he obtained two examples of the genre, a single tone and a double tone, from practicing Trinidad songsters. The single tone here is performed by two well-known Trinidad calypsonians – the celebrated Growling Tiger (Neville Marcano) and Lord Iere (Randolph Thomas) – together with Indian Prince (Robert Haytasingh), one of the few calypso singers in the twentieth century of acknowledged East Indian ancestry.

Carnival Today

Carnival today is big business, and celebrated all over the world. Daytime Mas—the more familiar contemporary carnival celebrations—grew out of J'ouvert (or Old Mas). As people started to have more money, the celebrations became more and more elaborate, culminating in the spectacle that we experience today. Today's J'ouvert celebrations are in general more lo-fi and community oriented—adhering to the origins of the tradition, by showcasing traditional music making and celebrations. J'ouvert as celebrated with JouvayFest in Brooklyn, for example, eschews electronic music and DJs for traditional tamboo bamboo bands and hand-held instruments. JouvayFest Collective's mission is to preserve and present classic Trinidad & Tobago style J'ouvert—the music, dance, costumes, food and history of the genesis of Caribbean carnival.

Sandra A. M. Bell, a 3rd generation Carnival costume designer, describes how she became involved in Carnival. Read the transcript.